Why ‘Nice’ People Do ‘Bad’ Things - Part Two

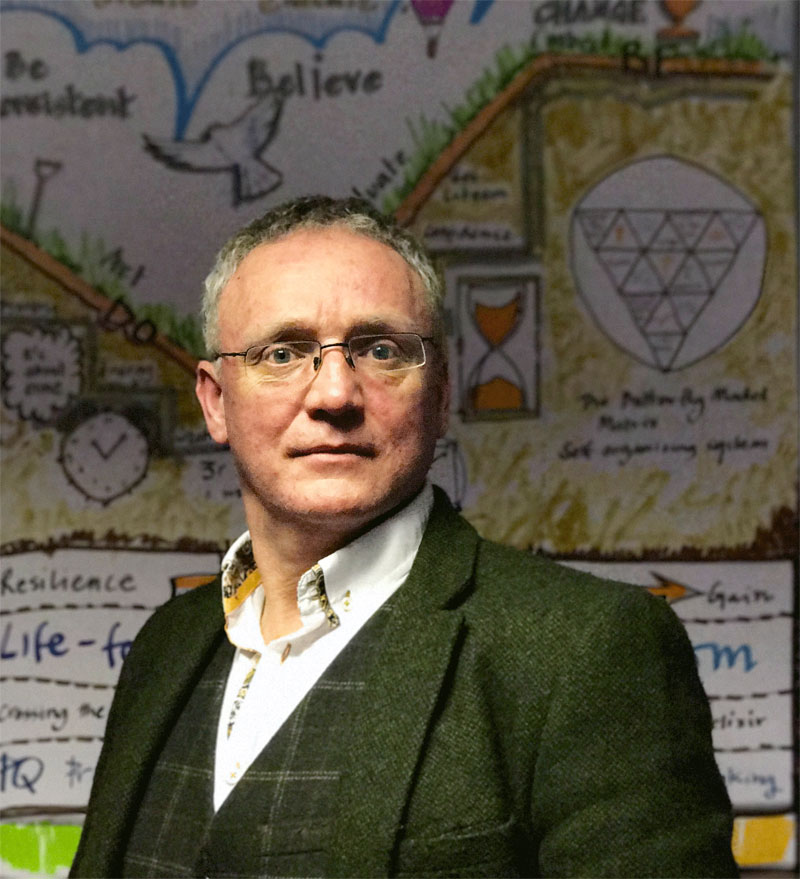

Associate Roy Leighton continues sharing insights from his work with the Cambridge University Peace Education Research Group into making schools happier, more peaceful places

In Part One of this blog, I highlighted how the people and strategies put in place to promote peace in schools maybe what is causing conflict and violence to go on and even get worse.

However, if we better understand the universal forces that shape us, our values and our world - time, relationships, resilience and results – we have more of a fighting chance to stop the fighting as it were.

First and foremost, we need to understand what sort of peaceworker we are and how those forces affect us.

As you read these descriptions, notice which ones resonate most with you.

The Peacekeeper

The peacekeeper uses clear and simple systems to provide clarity and rules in order to maintain and ‘keep the peace’.

They experience time by drawing from the past. Past might be the recent past or going back generations. Rules, laws, teachings are the foundation of peace in their book (and that ‘book’ could be a literal book, often religious in nature and origin, shaped by the words and minds of Gods, elders or the senior management team).

Peacekeepers love a handbook and clear guidelines, rules and hierarchs. For them, if everyone abided by the rules, we would all gain and the world would be a peaceful and loving place. The values of consistency, conformity, respect for authority, traditions and rules drive the narrative of the peacekeeper.

However, when we allow our peacekeeping values to become excessive, we deny our voice and the voice of others because we don’t want to be outside of the tribe, family or department.

We don’t want to break the rules because of the risk exclusion or shame. This faith in ‘the book’ and an unquestioning acceptance of enlightened, knowledgeable or ‘wise’ leaders, paves the way for less scrupulous individuals to take advantage of this collective obedience and hyper-rational mindset.

Here, rules, policies and laws are imposed (directly or indirectly) on a compliant community to keep them in their place. These so-called leaders, gurus and anointed ones introduce ideas and stories that stretch credibility but are embraced and embedded with zeal by their followers. Our current political situation, both nationally and internationally is, sadly, a perfect example of the excesses and violence of the culture of the peacekeeper.

As Voltaire said:

‘Those that can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.’

Change for the peacekeeper must not be a threat to their survival or a challenge to their beliefs, rituals or status. Their natural distrust of others - especially those they have no experience or knowledge of - means that if anyone from outside the tribe that presents an alternative way of being in, or seeing, the world are at best ignored or at worst ostracised or attacked (directly or indirectly).

The Peacemaker

The peacemaker uses a more complicated system that evolves as a consequence of the community needing to move to the next stage of maturity. This next level of growth is needed when order breaks down, the ‘rules’ are broken and order needs to be restored.

The experience of time for peacemakers is very much in the here and now. However, in order to bring peace, love and understanding into the present, peacemakers need to be able to reflect on the past and work towards the future. Peacemakers are time travellers. Past, present and future hold no fear for them. This ‘time lord’ mindset requires no small amount of skill, talent and training in restorative methodologies and the management of change.

A peacemaker uses a variety of tools and techniques to adapt to change and to solve conflicts, both internally and externally. The introduction and application of restorative practices is one example of peacemaking in practice.

Peacemakers focus on the social and emotional skills needed to rebuild peace when people find themselves in conflict with each other. They have a healthy balance between the ‘I’ and the ‘thou’, the ‘me’ and the ‘we’. Paradox for the balanced peacemaker is no big deal. They understand that within the conflict of opposing forces lies the possibility of peace, learning and understanding.

The primary values of the peacemaker are curiosity, communication and compassion. All good. However, sometimes, when things aren’t going to plan, the peacemaker needs to step in and take over. They have to fight on behalf of those who lack a voice (the 'done to' - see the restorative window in Part One).

However, by doing this, they risk challenging and upsetting others. Sometimes they have to step back and do nothing, as any intervention will make the situation much worse ('not done'). Sometimes they need to facilitate the peace process and show people how things work ('done for').

The ideal restorative approach is always ‘done with’ but there are many occasions where ‘done for’, ‘done to’ or ‘not done’ are exactly what is needed.

If stifled by a well intentioned but misguided need to keep the peace and listen to everyone’s side of the argument, when balanced compassion becomes debilitating sympathy for the pain and distress of others, peacemaking collapses and a culture of negative peace is created.

And as we saw in Part One, negative peace is no peace at all.

In the case of the peacemaker failure to act is often less a case of others manipulating the systems and more about the peacemaker falling into ‘saviour syndrome’ (they see themselves as the only enlightened one in the room) not addressing their own negative nature or 'dark side', as Carl Jung (and Darth Vadar) call it.

When we are so enamoured with how we are seen by others in the world, when we want to be loved, respected and applauded for our mighty works, we can become sanctimonious, egotistical and driven by the superiority of our own status, beliefs and values.

Those with an unhealthy attachment to the excessive and destructive characteristics of the peacemaker need to be able to move beyond the complicated world of peacemaking and into the next level of awareness of peacebuilding with all the chaos and complexity that entails.

The Peacebuilder

The Peacebuilder introduces new disruptive and complex strategies into the mix in order to respond to emerging needs, desires and challenges generated by the conversations and constructive conflicts of the peacemaker stage of restoration and growth.

Peacebuilding activities, processes and exercises are invested in regularly and with a clear shared and agreed purpose. These Peacebuilding structures vastly reduce the need to rely on the rules and control of a peacekeeping culture and the restorative interventions of the peacemaker. A peacebuilding community functions at a level of maturity, awareness, and kindness that is adaptive and self-organising.

Time for the peacebuilder is very future focused. They can, and do, draw from the past and the present but their motivation is to prepare the conditions and systems for the future.

A peacebuilder doesn’t separate themselves from others and the world. They see themselves as totally interconnected and interdependent with the world and everyone in it. They are both separate and deeply connected.

This paradoxical state of total interdependence is known as biophilia or being ‘in love’ with the world. But, as Freddie Mercury warned us, ‘Too much love will kill you every time.’

When we sacrifice ourselves in service to others and the world (as saviours do) at some point, something has to give. Fatigue and frustration force us to forget our values and shared purpose and we regress into survival mode.

The reason, therefore, why ‘nice’ people do ‘bad’ things is that they attach themselves too much to one of these three levels of being and don’t adapt to the reality of the moment. They become fixed to one way of restoring peace and removing conflict which will only lead to more destructive conflict. They act to protect their own security, ideas and identity by attacking or undermining the actions and ideas of others. Sometime consciously but more often than not they are unaware of the destructive manifestation of their values and drives.

When this happens they diminish their own authenticity and credibility and negative peace becomes the norm. Not nice.

To sum up, the peacekeeper becomes a barrier if they do nothing because they don’t want to upset things, break the rules or be seen as a failure. The peacemaker becomes a barrier when they do nothing because they want harmony and love at any cost. The peacebuilder is less susceptible to the negative manifestations of their character. They are, for the most part, happy to disrupt but fatigue, demands of the tribe and deadlines can plunge even the most insightful person into negative behaviours.

The simple reason we find ourselves unaware and out of balance is that we allow our values to become excessive and, if not checked, they become destructive.

Negative Peace

That’s it. It’s not that we don’t have values, but that we too often fail to see when we have shifted from creating value to adding to the anti-value culture of negative peace.

So, how do we reduce the risk of creating a culture of negative peace? How do we return to the simple processes and healthy values we all agreed on at the beginning of our journey? How do we change the narrative of violence to one of positive peace?

The starting point is to find the things that connect you.

For me, it is stories and the power of play. Listen to and tell the stories of the past that may have been forgotten or suppressed. Listen to and tell stories of the present that we may be keeping to ourselves. Listen to and tell the stories of the future you want to see and the adventures and challenges that lie ahead of you.

And whist listening, let everyone speak. Not just the loudest.

To find our more about my work in schools around building peace and community, then please get in touch with the nice people at Independent Thinking and we can arrange a time to chat.

In the meantime, remember, love isn't all you need, but it's a good place to start. [ITL]

To find out more about booking Roy Leighton for your school, college or organisation call us on 01267 211432 or drop us an email on learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

Enjoy a free no-obligation chat.

Make a booking. Haggle a bit.

Call us on +44 (0)1267 211432 or drop us a line at learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

About the author

Roy Leighton

Roy and Independent Thinking go back a long way. He is an inspirational speaker, a recent graduate of Cambridge MA programme and the author of many books around the processes of change, growth, creativity and making schools more humane places.