Why ‘Nice’ People Do ‘Bad’ Things - Part One

Associate Roy Leighton shares insights from his work with the Cambridge University Peace Education Research Group into making schools happier, more peaceful places

"People are the hardest part of change."

Mark Finnis, Independent Thinking on Restorative Practice

If you're reading this it is because you know that if anything needs transforming, it is the culture of conflict and exclusion, inequality and violence in our schools and communities.

But transformation is not for the fainthearted.

Those engaged in changing this negative narrative are some of the nicest people you are ever likely to meet. The best interests of the children and families that they serve are at the heart of everything they do. They invest in a multitude of restorative, human-centred approaches to create a culture of inclusion for all.

So, why is it that so many restorative programmes flounder and too often fail?

The issue is that the very advocates for peacebuilding, restorative practice and change are, too often, the barriers to achieving it.

The Power of 'Done With'

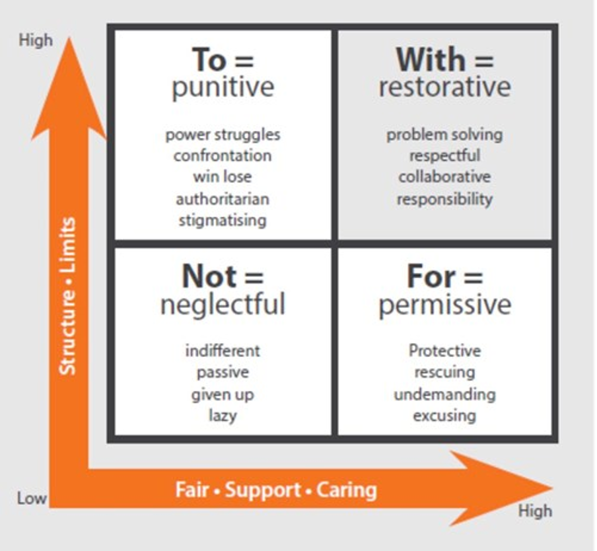

Take for example, the diagram you might recognise from restorative practice. A significant reason for the lack of success in building and sustaining a restorative culture is because the restorative ‘done with’ quadrant of the restorative window has become, for many, their fixed and primary focus.

At first glance the punitive ‘done to’, neglectful ‘not done’ and permissive ‘done for’ quadrants are seen only as entirely negative.

However, just as the restorative ‘done with’ quadrant has its light and dark side, so too do the other three more obviously negative quadrants contain the embers of potential enlightenment, learning and social cohesion.

As the former co-chair of the Cambridge Peace Education Research Group at Cambridge University (CPERG), I’ve had the good fortune to engage in many robust conversations with peace scholars from around the world about the causes of, and possible solutions to, conflict and violence in schools, businesses and politics.

What is both fascinating and disturbing in equal measure is our counterintuitive finding that it is the avoidance of conflict that creates the conditions for violence.

Central to my own research and practice are the ideas and principles of the founder of peace and conflict studies, Johan Galtung.

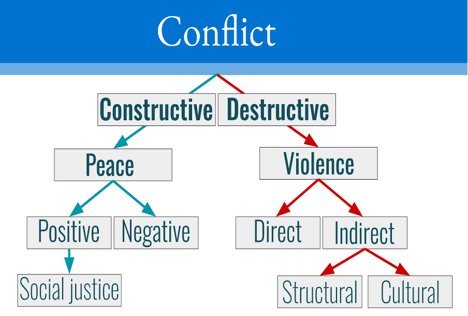

In 1970, at the Second International Futures Research Conference in Norway, Galtung presented a paper entitled ‘Pluralism and the future of human society’. In this paper he shared this peace and conflict model (see diagram):

Essential Nature of Conflict

Galtung’s model recognises that conflict is central to all human (and non-human) interaction and vital for healthy and mature growth - personally, collectively and ecologically.

In other words, conflict can be constructive or destructive. It all depends how we react to it.

When we respond to conflict in a destructive way it leads to violence that can be expressed directly (physically or verbally) or indirectly (institutionally and culturally).

However, when we respond to conflict in a positive and constructive way, it can lead to healthy growth and dynamic change. - and yes, to peace.

According to Galtung, peace has two pathways:

- Positive peace, which creates social justice.

- Negative peace which sits in the no-man’s land of social justice and violence.

Negative peace is not peace. It is simply the absence of direct violence. Institutional and cultural violence are still alive and kicking but people are unaware or, if they are aware, they choose to ignore them. The values of kindness, inclusion, collaboration and harmony that are at the heart of so many teachers means they don’t feel comfortable to speak up or shout out. They are too ‘nice’. The very values that begin the journey towards restoration and peace, when they become excessive and destructive, open the door to failure and violence.

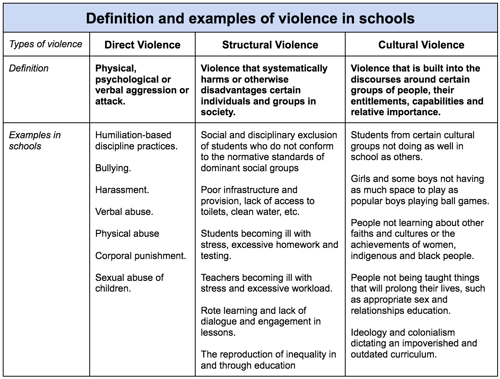

In their excellent book Positive Peace in Schools fellow CPERG (Cambridge Peace Education Research Group) scholars, Professor Hilary Cremin and Dr Terrence Bevington, give examples of what direct and indirect violence looks like in a school setting. Have a look at the table below and do a quick mental check to see if you have ever seen or experienced these examples of direct, structural and cultural violence:

Unless we can see when the values that we hold and inform our view of the world shift from being creative and constructive to excessive and destructive, we will have little hope of building a restorative culture of positive peace and sustainable change.

Attachment to Values

It’s not a lack of values that stops peace and reconciliation in its tracks - it’s our attachment to values and beliefs that have become out of balance and violent.

To change the narrative we have to be conscious of how we are influenced by the four universal forces that shape us, our values and our world. These forces are:

- Time

- Relationships (self, others and the environment)

- Resilience (learning, maturity and the management of change)

- Results (tangible outcomes).

In Part Two, I will share a short summary of how these forces are experienced by the three kinds of peaceworker.

To find out more about booking Roy Leighton for your school, college or organisation call us on 01267 211432 or drop us an email on learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

Enjoy a free no-obligation chat.

Make a booking. Haggle a bit.

Call us on +44 (0)1267 211432 or drop us a line at learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

About the author

Roy Leighton

Roy and Independent Thinking go back a long way. He is an inspirational speaker, a recent graduate of Cambridge MA programme and the author of many books around the processes of change, growth, creativity and making schools more humane places.