Getting Assessment Right II

Source Analysis

Back in June last year, I wrote a well-received blog about assessment across the curriculum.

It looked at how we assess in subjects like history and geography (not to mention art and design) and focused on the use of source analysis as a summative assessment point.

As with anything that goes on in school, there’s never a point at which we can sit back and claim we’re completely happy with everything we’ve done.

There are always developments to be made or adaptations to be considered and this is definitely the case when it comes to assessment.

A Tweak and a Nudge

Over the past few years, we’ve tweaked our approach to summative assessments so that they better capture how well the children are learning the curriculum.

One example of this tweaking has been not so much in the selection of the source that we plan to use for our assessment, but in how it’s presented.

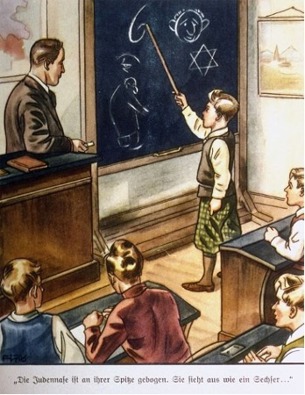

When we first started to experiment with this approach to assessing across the curriculum, we gave limited prompts or direction to the children. For example, in year six, the children study 1930’s pre-war Germany, and as a summative assessment point, we might have presented them with a source like this controversial but indicative image.

We’d trust that as we’d built up their knowledge thanks to a specified and well-sequenced curriculum, they would just crack on, analyse it and show us what they knew.

We’d trust that as we’d built up their knowledge thanks to a specified and well-sequenced curriculum, they would just crack on, analyse it and show us what they knew.

For some children this worked well enough, but for others it was more of a struggle. For these children, their responses were either very limited or narrow.

We found that the children could ‘say what they see’ but often didn’t draw on wider knowledge from other aspects that they’d studied.

It felt like we needed to give them a bit more to go on – something to focus their thinking and nudge broader recall of the content.

One of the first things we looked at were the ways in which assessments were presented in KS3 and 4.

We realised that it was unusual to find assessments that didn’t give some context to the thing the children are looking at.

A Commemorative What?

If we think about the source above, it would help to have some commentary about it to help the children understand what it is. For example, we could say:

This illustration is taken from a 1938 children’s book called The Poisonous Mushroom. The boy is drawing a nose on the board and the caption reads: ‘The Jewish nose is crooked at its tip. It looks like a six'.

This might sound obvious but it surprised us that, even with seemingly straightforward sources, there could be uncertainty from the children about what they were looking at. (A great example of this was a commemorative stamp that we used as a history source in Year 5. The staff all knew it what it was and what it was for because, hey, we’re grown-ups. The children, on the other hand, didn’t have a clue!).

Such uncertainty can be easily fixed by just telling them.

Whatever it is they are looking at should be familiar anyway (i.e. they should have come across other similar sources throughout their project), but just to make doubly sure, we’d state it clearly to avoid any guesswork.

Along with providing some context (or telling them what it is), the other common feature of KS3/4 assessments are some kind of question prompt that helps to elicit the knowledge that’s being assessed.

Construct Under-Representation

Now, the danger with this is that as soon as you come up with a question about the source, you’re potentially narrowing the scope of the assessment.

Let’s say we go for the following question:

How was education used as a form of indoctrination in 1930’s Germany?

It’s not a bad question (we can clarify the language in it to make sure they understand the work indoctrination, of course.) but it’s only useful if the only thing we’re interested in assessing is their knowledge of education as a form of indoctrination.

In terms of assessing anything else about the period, it suffers from ‘construct under-representation’. That is to say it only assesses a small aspect of the stuff we’ve taught.

The children can talk about what they can see but it doesn’t go out of its way to encourage them to draw on any wider knowledge.

To help avoid this narrowing, we can tweak the language in the question to open it up, as follows:

How far does this source explain the treatment of Jewish people in 1930’s Germany?

And then just to make sure…

Use the source and your knowledge to explain your answer.

In terms of what the children are looking at, they can not only talk about what they can see – the information that the source shows - they can also tap into aspects of their learning that are not shown in the source.

All thanks to a question that encourages them to look at the bigger picture.

What's more, to answer the question well, we’d want the children to recognise that the source is actually pretty limited in terms of explaining the treatment of Jewish people.

We’d want them to know that education was just one (albeit powerful) form of prejudice and discrimination (the ‘Does show’ column) and be able to give some examples of others (the ‘Does not show’ column).

We could show this by way of a two column box as follows:

|

Does show: |

Does not show: |

|

· Aryan children · Education used to indoctrinate · Jewish people portrayed as inferior/abnormal/ugly

|

· Wider examples of propaganda (Newspapers, Radio, Newsreels, banning/burning of books) · Impact of Nazi legislation, Nuremberg laws – removal of citizenship/rights/civil liberties etc.

|

Beyond this, for our deep historical thinkers, there’s also the opportunity to respond to another aspect of the question in order to demonstrate their understanding of second order or disciplinary concepts in history.

Big Ideas

The phrase ‘Jewish people’ within the question is something that historians would view as an unhelpful generalisation.

When dealing with disciplinary concepts in history, we present them to the children as ‘Big Ideas’.

And one of the big ideas in history is the concept of ‘similarity and difference’.

This concept is sometimes misunderstood as a ‘then and now’ or ‘past and present’ comparison rather than its true application which is to help us understand the similarities and differences between people (and groups of people) in roughly the same period.

(If it’s ‘then’ and ‘now’/’past’ and ‘present’ you’re after, then it would be the Big Idea of ‘continuity and change’).

In the context of our question, the treatment of Jewish people varied depending on factors such as geographic location, local authorities, and the specific stage of Nazi anti-Jewish policies.

This meant that in some cases, Jewish individuals faced discrimination, economic persecution, and violence, while in other instances, they were subjected to mass deportations and extermination.

Through our scheme of work, we’d want to explore (in some way) the diversity of experiences in the hope that this might inform the response the children give to the source.

Of course, we’re talking ‘cherry on the top’ here.

For us to be able to say that a child is learning the curriculum well, we’re after them demonstrating that they can recall and apply their knowledge - a combination of the two columns above.

Any more than that and we’d be over the moon, but you never know.

If you wanted to help this along a little, there wouldn’t be anything wrong with referring to the specific Big idea you were interested in as part of the question. Something like this would work:

Try to build in the Big Idea of similarity and difference to your answer

Some children might pick up on it, others won’t – at least the opportunity is there. [ITL]

If you'd like to know more about Jonathan's whole-school approaches to assessment across the curriculum, he'll be running another webinar on the topic on June 20th 2024.

Sign up details are here.

And to find out more about his whole-school curriculum-wide approaches to primary teaching and learning check out his latest book, The Monkey-Proof Box, published by the Independent Thinking Press.

To find out more about booking Jonathan Lear for your school, college or organisation call us on 01267 211432 or drop us an email on learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

Enjoy a free no-obligation chat.

Make a booking. Haggle a bit.

Call us on +44 (0)1267 211432 or drop us a line at learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

About the author

Jonathan Lear

Jonathan Lear is a highly skilled and experienced teacher and deputy head in an inner-city primary school who is rewriting the rules when it comes to curriculum design and delivery. He is the author of Guerrilla Teaching and the Monkey-Proof Box.